It’s like someone is in my face yelling at me in German. I can kind of grasp if they’re happy or sad, but I don’t speak the language enough to truly understand what is being said.

A few months ago I began a process that would ultimately change the way I view myself, and my place in the world. In many ways, I’m still trying to process what it means to me–and the conflict of whether to disclose this discovery to my wider world.

I have chosen to publicly disclose, and to do so here to anyone with interest in the subject. I do so in the understanding that there is a great deal of misconceptions regarding the topic, and it is my hope that through this disclosure I am able to create better understanding of my experience. This blog contains only what I know to be true of myself. There are as many presentations of the condition as there are people who experience it.

This is my experience as an autistic woman.

Say what?

Yes, you read that correctly. I have been assessed as presenting with enough significant traits of Aspergers Syndrome to satisfy a formal diagnosis. I don’t much like the word ‘Aspergers’–not so much for the Sheldon Cooper connotation, more I just don’t like the combination of letters in it.

One of the key misconceptions about those with Aspergers is that they are fundamentally more capable than someone defined as simply ‘Autistic’. In the DSM-5, the leading diagnostic manual for mental conditions, ‘Aspergers’ has been removed as an independent diagnosis. I like that this opens the door to a much broader understanding of ‘Autism’, the capabilities and weaknesses of those who experience it.

So–are you ‘high’ or ‘low’ functioning?

This is another reason why removal of the ‘Aspergers’ label is important. The idea that some autistic people are more intelligent, more capable, and more useful to society is dangerous. It leads us to expect that those defined as ‘high’ functioning should be able to adapt to the neurotypical world and survive without any compensatory methods. On the other end, it allows us to believe that ‘low’ functioning persons have diminished value due to their autism.

This is especially true of those who are ‘non-verbal’. That is, someone who is functionally able to speak–but experiences an autism-related block that prevents them from conversing in a ‘normal’ manner. Their inability to speak has no relation to their intelligence or what they can contribute to the world. Many are very talented writers and express themselves through text.

Autism is not fundamentally an intellectual disability, though it can be for some. Therefore, those with autism should be approached and classified according to our unique strengths and weaknesses. Just like anyone else.

I am neither high, nor low functioning. I am a person with an autistic brain.

Then… what is autism?

Autism is a different operating system. It’s a way of thinking that is atypical compared to the general population. It is the experience of looking at the world, and knowing you see it differently to everyone else on the same bus.

In practical terms, autism is a profile of intense strengths and crippling weaknesses. What those strengths and weaknesses are varies across individuals. Although everyone on earth has strengths and weaknesses, those with autism experience a much greater gap between what they are good at, and what they’re not so good at.

For example, a ‘neurotypical’ (someone with a brain that functions the same way as most) or ‘allistic’ (someone who is not autistic) person may be ‘good’ at running and ‘bad’ at cooking. An autistic person with those same traits would be ‘amazing’ at running and ‘horrendous’ at cooking. The difference in skill (or lack of) is much more pronounced in someone with autism.

For me, I am excellent at writing. This is my primary method of communication and of untangling my own thoughts. I’m great with music–I have a natural sense of rhythm and ability to play instruments with deep expression. I have mostly untapped artistic talent. I am wonderful at conducting deep analysis, I can research a subject thoroughly and output text that allows others to grasp the concept. I can argue almost any point convincingly–if I can do it in writing. I can teach myself to do things. I find something to get excited about on almost any topic. Don’t believe me? I can even get passionate about cricket. I am loyal, enthusiastic, and I love streamlining processes and finding ways to make things more efficient.

I sound pretty wonderful, huh? Here are some weaknesses.

I am downright shocking at communicating directly with people. I tire out fast and become unreasonably emotional when I’ve gone past my ‘limit’. I need extreme amounts of solitude to recover. I don’t deal with light or noise particularly well. My ‘processing’ speed is much slower than the average person–I often don’t comprehend what you’ve said until a few seconds after you’ve spoken. I can’t deal with too much verbal information. I need time to sit back and make plans for things. I don’t handle plans changing. I don’t like situations that are vague. Often, I take instructions too literally or fail to consider beyond the task that was initially asked. I almost always miss the ‘hidden’ meanings in conversations. I am naive, overly trusting, and very… very easily hurt.

How much of that is autism, and how much is just… you?

Some traits are more likely to present in autistic people, but for the most part, these are things that are experienced by most people. It’s the combination and intensity of these traits that defines whether a person is autistic or not. It’s also in the reactions to these traits where the clues to autism lie.

All of the things listed there as strengths are things I am exceptionally good at. All of those weaknesses have the capacity to (and have) interfere with how I relate to others and the world around me.

So let’s look at some of the traits in detail, and I’ll explain what I mean.

Obsessions and special interests

When someone says ‘Aspergers’, most people think of an uptight person who is fanatic about one or two topics. Thanks to The Big Bang Theory, they most often think of Sheldon Cooper. This is most often true of persons with autism.

My interests were simple. I love stories. I still love stories. I will go to the ends of the earth for a good story.

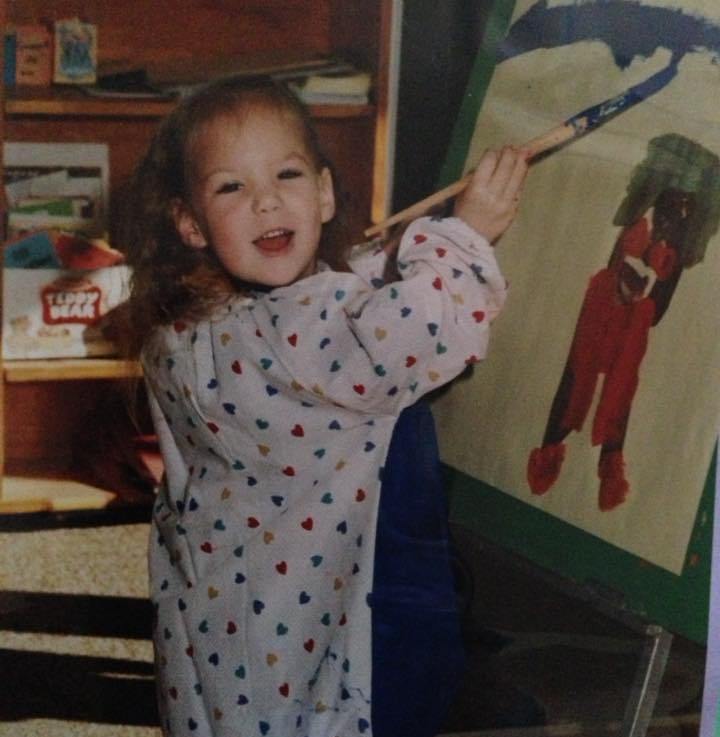

This began my obsession with books (and collecting books) and writing. I picked up the ability to read very early in life, well before I started school (thanks to excellent parents!). My obsession with words and letters is a sort of sub-interest to this, and it’s all sort of branched out into a broader love of linguistics, communication, and the history of the English language. It fascinates me. But it all started with stories.

This love of stories has also evolved into a love of TV, movies and video games. The creation of fiction is one of the most beautifully human things we have in our world. Through it we can imagine worlds beyond our immediate reality, glimpse into the future and revel in the past. We can escape where we are, imagine things greater, and even brainstorm solutions for problems that don’t yet exist. Writing is a form of pure magic.

Music was another early obsession. The first ‘favourite song’ I remember was Lover [You Don’t Treat Me No Good No More] by Sonia Dada. I loved the deep vocal tones and the beat. The child-friendly tunes of Peter Coombe played constantly through early life, and my first favourite movie was Disney’s Fantasia. Music is a language of its own that captures stories both explicitly and imagined in the listener’s mind. On my worst days, music is a soothing force that brings me back down.

My third and most obvious obsession as a child was cats. I used to be able to list breeds and their characteristics. I had books and toys and a collection of ornaments–if ever I rattled on about something (as ‘Aspergers’ is known for) it was about one of these topics.

These interests evolved and shifted over the years. I’m fascinated by true crime now, with psychology and technology. I like to know what features new gadgets have, how new apps can change the way we do things, and what goes through someone’s mind when they commit a crime.

I am also interested in what interests other people. I have a deep desire to understand what draws people to one topic or another, and thanks to my ability to find something of interest about almost any topic, I’ve discovered love for subjects that are outside of my general ‘sphere’ of interest. Much of this was sport related, AFL and cricket, but also crafting tidbits and politics.

Why research something you’re not really interested in?

Good question. That leads back to another trait: I struggle to make general conversation with people around me if I am not adequately prepared to do so.

It started as a means of ‘having something to say’. I feel a strong sense of disconnection even around people I’ve known a long time, and particularly those with whom I don’t share a common interest. Talking about my own interests is generally not advised–I find they’re very specific to me and not of great interest to other people. Plus, if you get me started I’m rather hard to stop.

I also don’t see much value in small talk. It was a part of the ‘cashier’ routine that I had to do for work, which I think cheapened it even more. In the job it became reflexive and ingenuine. People talk too much as it is, I don’t see any need to waste words about the weather when I could be making a proper and meaningful connection with the people who matter.

So I began researching tidbits of information that fell into their interests. Facebook makes this incredibly easy! Facebook is literally a feed of things other people are interested in, articles you can read and videos you can share. This is one of my best compensatory methods and is invaluable in helping me to begin and carry conversations.

Do you have emotions?

That’s another misunderstood trait. Autistic people often have trouble processing or reading emotions from other people, and also in expressing the emotions they feel. That’s not the same as not having emotions.

I feel the state of others around me keenly. It’s like a thick fog–I can’t avoid it. This ‘empath’ trait is sought after and is linked to emotional intelligence. Except in my case (and in the case of other empathically sensitive autistic people), although I’m getting the information–there’s not much I can do with it. I don’t understand it.

I understand the basics of it. Good emotion, bad emotion. Beyond that, I’m lost. It’s like someone is in my face yelling at me in German. I can kind of grasp if they’re happy or sad, but I don’t speak the language enough to truly understand what is being said. All I know is it’s right in my face and it’s damn uncomfortable. When others around me are stressed or upset, I begin to get stressed and upset because of the tension, and not knowing how to release or break it.

Like many autistic people, I don’t read faces, tone, or situations well. So all of that information is just confusing and makes it hard to cope. There’s a constant analysis going on in the back of my brain, trying to discover the meaning as it unfolds. This is a skill that is acquired over time and experience, and while I’ve got better at it over the years, it’s still exhausting and far less accurate than that ‘intuitive’ understanding that allistic/neurotypical people have.

As for my own emotions? They’re strong. Incredibly so. There are two forces here that make it hard for others to understand my emotive state, and one is simply that I am terrible at making the right face at the right time.

I am a severe sufferer of ‘resting bitch face’. Often I have to consciously change my expression to reflect happiness or sadness, and this I do solely for the sake of not looking ‘weird’. Left to my own devices, my face would rarely shift. The same is true of inflection in my voice, I have to remember to speak in a way that ‘matches’ how I should be feeling.

The second is practice at stillness. This is an unrelated and learned skill. When I was bullied in early school years, the first advice I got was to never let them see me cry. I went far beyond that and taught myself a poker face that (combined with inborn reduced expression) I presented to the entire world.

There are days where I am incredibly expressive. I express myself outside of facial expressions, too–I run and jump and spin and talk a million miles an hour. These are the days when I am most myself, and most comfortable being who I am. When I am being ‘weird’ I don’t have to be ‘still’ and I can let go.

I struggle with letting go a lot. A lot. Experience tells me that if you act outside of what is expected, only bad things will happen.

How do you handle conversation?

To be honest? Not well. Unless it’s on a topic that I know a lot about, or have researched, I struggle. My slower processing speed can make it very hard to keep up with the pace of a conversation, and before I say anything, it needs to be formed, checked for appropriateness, and rehearsed in my head before it leaves my lips.

If I don’t go through that process–you never quite know what I’ll say. I can spurt out irrelevant or even offensive things without meaning to. I have to actually think quite hard about what is okay to say in front of the audience I’ve got, and to word it in a way that can’t be misconstrued. When you don’t really understand the extra connotations that others spot in terms of word choice, facial expression and tone of voice (remembering that mine does not flow naturally!) it becomes very important to watch what you say.

There are so many social clues and contexts and hidden meanings that I just… don’t comprehend. It’s only recently that I learned that commenting on how nice someone’s food looks/smells is the same as asking for some. I didn’t know that–and I would often compliment my housemate’s cooking based on the sight and smell. Not in the slightest did I expect that I should be offered some. I just wanted to say something nice based on an observation. That food did smell good!

In short, any of those more subtle aspects of interaction I need to learn the same way as I learned to tie my shoelaces: with practice and experience.

Starting conversations is probably the hardest for me, especially if they’re about myself. Those of you who primarily encounter me through this blog and other online channels might think that’s absurd. All I do here is talk about myself!

In person, it’s a very different story. First, it’s much easier to start a conversation that is light hearted and that you know will be well recieved by your conversation partner. So if I start conversations, it’s more likely going to revolve around their interests.

The second thing you need to understand, is that I’m driven by a deep and unshakeable fear of rejection. I’ve had this constant knowledge all my life that I am somehow different, that I don’t function in the same ways as other people, and for the most part I’ve been deathly afraid of demonstrating that difference. I fear that when people come to know me as I see me, they will see ‘that’ thing that makes me ‘other’ and that will provide enough reason for them to turn away.

I’ve always wanted to be out of the spotlight, away from scrutiny, scared that any minute I will be discovered. It’s felt a lot as if I’m some sort of alien trying to masquerade as a human, trying to learn their ways and fit in but never quite managing it. Fearing every time I slip up and show myself that I’ll be hunted down and outcast once and for all.

That’s a pretty heavy belief to have when you’re seven or eight years old, yet it’s one of the oldest ones I have. I don’t remember ever feeling any other way. I didn’t believe I had a right to be myself, because what I was was obviously ‘wrong’ and didn’t fit here.

The people I struggle to talk to most are the ones in my physical realm. Online is online. Yes–I have amazing friends that I hold in very high esteem and my life would not be the same without them. But even so, if, when I reveal my true self to them, they shun me?

I can turn them off. The internet is full of block and delete buttons. The emotional cost will still be high, but I won’t run the risk of seeing them down the street. They won’t be at family gatherings. I can tell them anything I like with that safety net.

I also get to speak with them using a method that allows me the most clarity: via text. I very rarely speak the more difficult things. When I do, the right words never seem to fit in my mouth, or I sway the conversation to make light of things and change the meaning entirely. Spoken conversations never go the way they should. I always end up saying something I didn’t mean, or not explaining things well enough and the whole exercise ends up being pointless.

This blog allows me a medium. It’s open and visible to people in my physical and online realms alike. These are my words as I wish I could speak them, explaining myself in the way I’ve always wanted to–and far more powerfully now that I have some understanding of why I am the way I am.

What do you mean ‘slow processing speed’? You’re smart, right?

For a given value of ‘smart’, yes. I’m great at navigating photoshop, but at this point in my life I can’t drive. People far less switched on than me can drive, so why can’t I? That’s the trouble with the ‘smart’ label. It assumes that smart in one thing is smart in all things. I am definitely not. No one is.

I have definite intellectual strengths. However, it can take me a little longer to get there. How fast or slow you process things has nothing to do with intelligence.

It’s a bit like RAM in a computer. If the average person has 16GB of RAM, I’m probably running on 12GB. Therefore, I am less efficient in how I deal with things around me. My extreme sensitivity also means that a lot of that ‘processing power’ is taken up by interpreting information from external sources. So there’s very little left to deal with the immediate situation.

This is most obvious in conversation. I have particular trouble with ‘verbal information dumping’, or basically when someone gives me a lot of instructions or ideas in a single conversation. In transferring that information from the short term (or RAM) to long term (HDD, haha!) memory, there’s not always enough RAM/short term memory to store the information… and pieces get lost.

Thankfully, there’s also a weird ‘transitional’ memory that I’ve noted, which is kind of like a backup for the RAM/short term. It doesn’t catch everything, but often if it’s been a long day full of information or if I’ve been given a lot of options regarding something, during my next quiet moment I’ll take some time to go through all of the concepts that were presented and process them properly.

This is generally what I’m doing while staring at the TV, playing video games, or scrolling through Facebook. I’m going back through the day and consolidating my memory.

What do you mean ‘extreme sensitivity’?

My sensitivity to almost everything is perhaps the least known fact about me. Even to myself, I didn’t realise what the source of discomfort was until it was pointed out.

I don’t tune things out well. That dripping tap? The radio across the road? That bird that hasn’t stopped for the last hour? I hear each instance as keenly as I heard the first. I have exceptional hearing, and the same goes for my sight and smell. But as I lack the ability to subconsciously tune out background sensations, my attention is constantly split between what is immediate and what is not.

I’m sitting at my desk right now and I’m hearing that bird, the fan in my computer, my fingers on the keys, that weird sound of the sky at night, cars move up and doors open, the neighbours in their pool, the saliva in my mouth. All of these have equal sized pieces of my attention.

I can feel my foot pressed against the chair, my hair prickling at the back of my scalp, sweat drying on my forehead and how itchy my nose is (my nose is always so annoyingly itchy!), my chest aching from a breath I was holding, my one roll of fat resting comfortably in my shirt, my bra straps itching across my shoulder blades, my trousers stuck to my leg with the heat. I can feel how heavy I am and how my hands shake when they come to rest. Again, none of these are ever tuned out. I am always this aware.

My vision is even more intense. I’m highly sensitive to bright light, and the fluourescent bulb above is reflecting off the white walls and table and box in front of me, a sharp contrast to the black computer screen, keyboard and tower. The black lines are wiggling and jumping around, creating after images in green and purple. The text on the screen is wiggling about like it does. How I ever learned to read, let alone love doing so, is actually a miracle. The granular colours of visual snow are drifting about, as usual. I’ve never known anything different. I’m now aware of how much it drains me, and how important sunglasses are.

Often it feels to me like my skin has been peeled away, leaving every nerve raw and exposed. Every sound is a booming cacophony, every touch is a hot knife. It drains and builds, reducing my tolerance to anything more until I literally can’t handle anything more. In those moments I need to escape. I need to drastically reduce the amount of sensory information coming in, or I will go into meltdown.

Meltdown? You have meltdowns?

Yes. That is the actual term for what I call ‘episodes’. It’s a release, an expression of being so incredibly overwhelmed that literally nothing more can be tolerated.

Mild meltdowns are shaking and crying, but they go far more extreme. Screaming into pillows and raking my nails up and down my skin, trying to distract myself from a weird feeling that I can only describe as thrashing around inside my skin. As if I can feel my bones shift violently about inside me, trying to get out. I can’t catch my thoughts in a meltdown, they’re fragmented and swirling in a hurricane. There’s lightning snapping at the synapses in my brain, making me think things I don’t want to think.

I am lucky, very lucky, that at the same time I often go into a sort of ‘paralysis’. I freeze and feel myself fighting under my skin, but come to no real physical harm. The desire for violent acts is there, I want to punch walls and kick glass and run out on the road and scream at cars–but I can’t, and I don’t. I don’t move until rational thought comes back to remind me how dumb those thoughts are.

Frustration is the strongest feeling. Frustration that I can’t control it. Frustration that I didn’t know where it came from. Frustration that this is a thing that doesn’t seem to happen to other people, and I must be broken for it to happen to me so frequently.

I experience some form of meltdown roughly once a week. A bad week will have them once or twice a day, some of them being very severe. The experience takes a huge toll on my energy and a long recovery time. Exhaustion also adds to the underlying stress that leaves me prone to meltdowns, so if one severe one occurs, more usually follow.

There’s no cure for this. No way to control it, but to observe how I’m reacting to the situation I’m in, and take steps to minimise overstimulation where I need to. It usually means stepping away in social situations, saying ‘no’ when I want to say ‘yes’, and generally avoiding too much sound and light than I can handle. That reduces the frequency.

They will always happen. That’s simply how it is.

Uhh… violent acts? That doesn’t sound fun.

It’s not. It’s really not.

Like many autistic people, I experience emotions at an extreme level. I react to situations in a very intense way that I don’t fully understand. There’s no real language to explain those moments. I know that I’m feeling something highly complex, and often there’s a strong desire to communicate what I’m feeling–but I’m left without the tools to do so.

One method of expressing this frustrating pain is to convert that feeling into a physical object, something that others can see and comprehend. It is in the world, it’s real, it’s not a figment of my imagination. Depending on my state of mind, the impulses range from scratching my skin to the above-mentioned running on the road.

I need to underline here that never in the almost-thirty years of having these types of thoughts have I acted on them any further than to scratch my arms and legs. Nor will I ever go beyond that. So much meaning is lost in the conversion from emotional to physical that it literally makes no sense to do so, and above all else, I am a highly logical being.

I have a ‘voice’ (not a real voice, but I often consider it a separate entity) that pipes up when intrusive thoughts jump their way into my brain. My more rational self poking holes into the violent suggestions that flash up like annoying pop-up advertisements.

The best example of this rational voice is from the day that the most bizarre intrusive thought suggested that I should take the office scissors and cut both my hands off at the wrists. I was having a bad day and feeling under a lot of pressure, things kept changing every other minute, and I was well beyond my limit.

Rational voice says: ‘Okay, so you very painfully cut through the bone of one hand with blunt office scissors… exactly how do you plan to cut the other hand off? You can’t use scissors with a bloodied stump, dickhead.’

I laughed. That’s often the case. Either rational voice points out how illogical/messy/plain dumb an idea is, or the gaps in the impulse’s logic are too hilarious. Either way, there has never been a chance of action on any of these more extreme thoughts. Nor will there ever be.

I bet you don’t like things changing around. Sheldon Cooper doesn’t!

I sure don’t. Some of Sheldon Cooper’s autism characteristics are ones that I do share. Rigid thinking and an inflexible sense of order are one.

I start my day with a sort of mental plan, a sequence of activities that will get me from waking and to the end of the day. I tell myself every morning that although I have this road map for the day, things will come up and I will need to adjust as necessary.

Haaaaaahahhaa. If only it worked that simply!

I get very frustrated with late changes to my plan. I’m quite okay with someone texting me 4-5 hours out from doing something that they’re now unable to, as that gives me enough time to process this information and adjust the plan accordingly. Texting me ten minutes before leaves me with a sudden gap in my mental schedule, and a sense of loss at how to fill it.

The same happens with being given activities to do. I need time to process that something must be added to my mental schedule, and time to figure out how I will best approach the task. Starting something the minute I’ve found out I need to do it is incredibly uncomfortable. It fills me with that unprepared sense of anxiety, not unlike the worry that you left the hair straightener on while you went shopping. I can do the task through it, but at the cost of that anxiety pushing me closer toward a meltdown. At the same time, the distraction caused by that unsettled feeling means I may not do the task as well as I normally might. I wasn’t prepared for this, I didn’t go in with a plan, and this is the result.

You might think it doesn’t matter, that not all tasks need a plan and approach–that I should just relax and do things regardless. In that case, you’re missing the point. Taking the time to mentally slot the task into my sense of order is how I am able to relax. I have a very defined system for how I go about the world, and the majority of it involves a period of consideration prior to action.

I even think for several minutes about what path I will take through the house before getting up to go to the toilet.

I don’t think there’s a single person I haven’t frustrated with this particular aspect of myself. Just ask my poor English teachers, who watched me sit in front of a blank page for hours before beginning to write!

So what is your ‘sense of order’?

Everything and everyone has a place and a way of being that I have come to expect. Changes to that can unsettle me very fast. One of my first major breakdowns spiralled from my family moving home–and I didn’t even live there at the time.

I get very attached to places and objects. Mum had the same microwave for so many years that their current one still looks wrong to me. I get upset when my favourite foods are discontinued. I hate when people change cars. Our local radio stations changed their names just the other week and I am not okay with it.

I love the idea of holidays, but the reality actually sucks. Everything is out of place at once. Christmas is a chaotic rollercoaster of visitors and nothing being the way it usually is. As much as I love the season and having people around, it’s not the norm and it becomes unreasonably stressful. During special events and holidays, I need far more time to recover than in an average week–purely because I have to keep re-creating my mental schedule around the chaos.

Do you understand sarcasm?

Another stereotype, and one that has a good real basis. I understand sarcasm from people I know exceptionally well. Sometimes. Not all the time. I understand sarcasm when it is hyperbolic and accompanied by a distiguishable ‘sarcasm’ tone of voice.

Our family is one that likes to tease each other in that good natured way that families do. I do it as much as anyone else, but even with family I have to second guess whether what they say to me is truth or joke. Or perhaps if it is a truth cloaked in humour. I never really know. I just laugh and try to think of something witty to say back. At least, now I do. I know that’s what is expected now.

Before I really understood that, I would shrink back or into a book and try to vanish. I would get offended or upset and retreat. What was fun for others was confusing and confronting for me, but I never knew how to express that feeling.

With people I don’t know, the confusion is a thousand times worse. Ask anyone who’s ever flirted with me–most of them get shut down so fast because I’m convinced that they’re playing some sort of joke on me. I get very defensive because I don’t fully understand what’s going on, and defensive is all I’ve got to protect myself with.

Do you hate social things?

Quite the opposite, if you’d believe that. I love having people around, even if it does get highly uncomfortable for me. There are certain environments that I hate, such as clubs and music festivals, but for the most part I’m extremely happy when surrounded by the people who matter to me.

There are ways I can push through, and the key one is alcohol. Alcohol dulls my senses and disables most of my filters, so I have a lot more processing power available to enjoy social situations. I refuse to lean on it as a social tool, but in situations where it is acceptable to drink and be merry, I do indeed drink and be merry.

The bonus of alcohol is that in disabling those filters, I’m generally more my authentic self and I don’t give a shit. It’s good training for being able to do that sober!

Why did you seek diagnosis?

I changed jobs, from a part time retail gig to a fulltime position as a marketing coordinator. Now, I have a long adjustment cycle for any type of change, but even when I normally should have been settled, I wasn’t.

I was experiencing difficulties I’d only encountered once before–when I was working full time as a network technician. I was tired and unfocused, unreasonably emotional all of the time, and I was struggling to get work done. When I got home, I would collapse on my bed and go straight to sleep. Most nights I was too exhausted to eat.

My productivity suffered for it, and I was beginning to think I was incapable of doing this wonderful new job. In spite of how much I loved it, I couldn’t seem to keep up with the changing priorities and multiple tasks that I was expected to have going at any given time. My brief foray into telemarketing was a complete bust, as I talked over people or said the wrong things, or worse–froze up when the conversation took an unexpected turn.

I had no idea what was wrong. I reached some very low points where my sense of worth was less than nothing. I contemplated returning to the job that provided me very little satisfaction and cried myself to sleep. How could I be so bad at something that I loved so much?

Many things happened in my fight to understand what was happening, but the key moment was an article shared on Facebook. It was on the ‘lost girls’ of autism, girls who were overlooked or misdiagnosed under the belief that autism isn’t something that occurs in females.

When I found a list of behaviours and symptoms, I just stared at the screen–and cried. I’d never read such an accurate description of my experience.

From there I went on a fact-finding mission, reading books and blogs and matching those experiences to mine. The result was almost always tears: of relief, because finally I wasn’t as weird as I thought. There were women out there just like me.

I wasn’t failing at my job because I was dumb. It was structured in a very different way to my previous job. I didn’t have the long gaps between short shifts to recover mentally. I was also working three times as many hours in a week, which is a lot for an autistic person. I shifted from being crippled by self-doubt to proud of what I had managed.

I am an autistic woman who is successfully holding down a full time job. Statistically, that’s quite an achievement! Many other autistic women are not able to manage full time work.

The choice to be properly assessed and formally diagnosed was a personal one. Because these autistic traits were causing issues at work, I felt I needed more than a Google search worth of answers. I needed solid strategies to help improve my productivity and create more balance in my life.

I did some research and located a psychologist who specialised in female autism. My experience with being allocated a local therapist was very hit-and-miss, so this way I was able to choose someone that I felt had the understanding I needed to give me useful answers. I read both Aspiengirl and Aspienwoman by Tania Marshall, and from there I felt reasonably confident that she could help me.

Tania Marshall does more than just diagnose, and as an adult, I needed more than just a label. Her view of Autism/Aspergers as a different wiring of the brain, and an opportunity to leverage super talents was one that I could get behind. Working with her I was able to understand both how I process things, and to begin building a road map toward better self management.

Are you glad you discovered your illness finally?

The process has been hard, and very confronting. The first thing I had to adjust on diagnosis was shifting the way I saw myself from having an ‘illness’ and ‘disorder’ with anxiety and depression, to being a person with a ‘condition’—a person with autism.

It may not sound like much, but the difference is huge. Autism isn’t something you cure. It isn’t something you can cure. I’m not sure I’d want to even if I could–it’s the source of my strengths as much as it is the source of my weaknesses. Like any other person, I need to manage those weaknesses and optimise my strengths. Unlike any other person, failure to take care of myself and to manage those weaknesses will result in a meltdown.

I’m very glad to have found this answer. So many things in my life make more sense through the lens of Autism. I struggle to let go of things before I fully understand how they occurred, so now that I have a better understanding of some of the more shameful events in my life, I can finally forgive myself for them. I finally know how and why they occured.

I can finally stop thinking of myself as broken, stupid, and a failure. Instead, I have been someone trying to survive in an alien world, living under the incorrect assumption that I should be able to survive the same way as everyone else.

I can’t. I need my own way, and that’s perfectly okay.

Importantly, I am not ill. I am just different.

Diagnosis for me meant that I was able to see more clearly the experience I have. It gave me the language to describe it to others. It gave meaning and hope that I could not just eventually be free of the more damaging effects–but manipulate my strengths into superpowers.

I always was and always will be autistic.

Isn’t everyone a ‘little bit autistic’?

Yes… and no. Everyone has traits that are commonly found in autistic people. But to say that everyone experiences them in the same intensity and with the same consequences as an autistic person is to completely disregard how painful and frightening a meltdown can be.

You might not like that itchy tag at the back of your shirt. For me, it will itch and itch and itch until I either escape it, or I break down.

Were you vaccinated?

Sigh. Yes. As you’ll notice, I also didn’t die of measles, mumps, or rubella.

The vaccination-causes-autism myth is completely bogus. There was never a time in my life where I was not autistic. The rise in autism diagnoses is due to the greater understanding of autism and its traits, not the increase in vaccinations.

Autism is primarily genetic. For any autistic person, there are family members who display fragments of autistic traits. Those traits are passed on, creating a profile that carries enough autistic traits for the individual to be deemed diagnosably autistic. The chance of my own children, should I have any, being autistic is incredibly high.

I will never understand the argument against vaccination on the grounds it causes autism. I would much rather this, than a preventable illness.

If you’re autistic, shouldn’t it have been caught in school?

For boys, this is most often the case. Girls are diagnosed on average two years later–and more and more women are discovering themselves at the age of thirty or higher. These older women (myself included) were in school at a time where the idea of girls being autistic was still a foreign one.

What happens in a lot of undiagnosed women is a cycle of not coping, where the woman is fine for a time–and then everything falls in a heap. There’s time for recovery, and then it begins again. It goes on until the woman goes into what is known as ‘autistic burnout’ or ‘autistic regression’.

Autistic regression?

Basically, a surge in autism symptoms. The individual is too run down or burned out to tolerate the things she did before, in the way she did before. Compensatory strategies that used to work are no longer as effective, and meltdowns become more frequent and more intense.

This is what drives most women to seek more answers. For me, changing my job was what drove me into a state of autistic regression, and I’m still trying to dig my way out of it.

Why can’t you just shrug it off and keep going?

Well-meaning advice suggests I should be able to tough things out, and push through. Some days, yes, that’s possible and productive. It’s not a strategy for the long-term, though.

Constantly pushing past my limits, not listening to my body when it demands rest, continues the cycle of not coping. It results in recurring burnout, each episode worse than the one before. In women who were not fortunate enough to be diagnosed, who continued trying to achieve things in the same way as their allistic peers, that burnout became permanent.

Nervous breakdowns, permanent fatigue, and critically reduced tolerance to sensory input? That’s definitely not a life I want to lead. So taking care of myself now, tolerating what I can and taking the time to recharge when I need to is highly important.

I need to accept myself as an autistic person, and make decisions accordingly.

How else do you cope?

I do a lot of things to cope on a daily basis. Wearing sunglasses (including inside at work), taking breaks during social activities, and having something I can hyperfocus on to ‘recharge’ if I can’t step away–those are some of the basics.

When I get home, I change into comfortable clothes that don’t cause excess sensory input. I spend my lunch breaks in a dark room, and you can usually find me resting with my eyes closed. Not asleep, but processing and blocking out the light for a while.

I get my nails done professionally, partly because it feels good and I like the uniqueness of it. It makes me feel like I stand out for the oddball that I am. But also because it flattens the tips and allows me to release pressure by scratching, without doing any damage. I get glitter polishes because watching the light sparkle is soothing to me, and can help stabilise me when I don’t have the ability to retreat.

I try to walk a line between avoiding things that induce meltdowns, and maintaining an active life. That’s a balance I’m still learning.

How are you still rambling?

I honestly don’t know. I hope this gave you a bit more insight into my world of Autism. I would love to answer any questions you have, or hear your own experiences.